The real conversation isn’t whether seed oils are “evil.” It’s whether fats are selected intentionally, protected properly, and used responsibly within a formulation.

When oxidation is managed correctly, shelf-stable foods can deliver quality, safety, and flavor—without sacrificing performance or consumer trust.

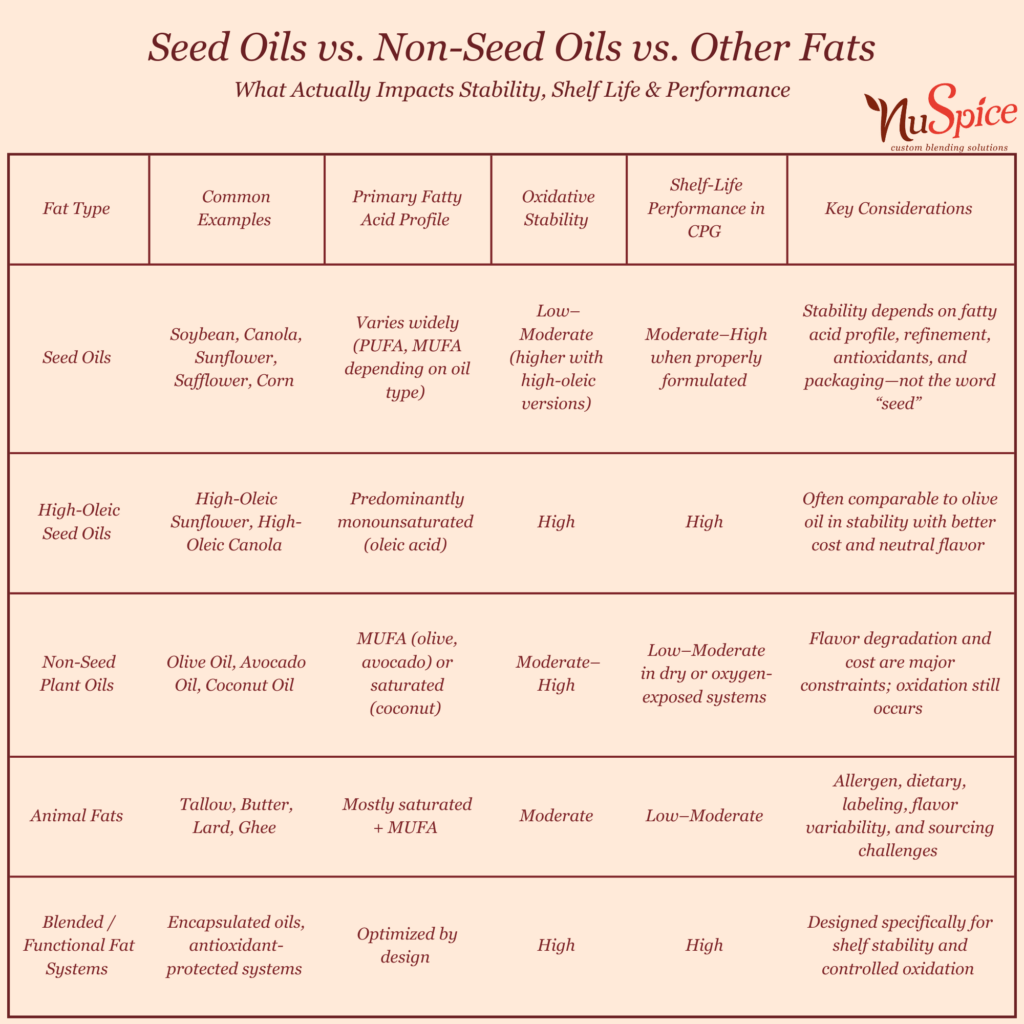

Seed oils have become one of the most polarizing ingredients in today’s food conversation. Once viewed as a neutral, functional fat source, they are now frequently blamed for inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and declining health. Social media soundbites and wellness influencers have amplified distrust toward oils like soybean, canola, sunflower, and safflower—often without distinguishing between oil type, processing method, or real-world application.

But as with most ingredient trends, the reality is far more nuanced. To understand where concern is valid—and where it becomes oversimplified—we need to move past ingredient labels and focus on oxidation, formulation context, and shelf-life expectations.

Why Seed Oils Are Under Fire

Much of the criticism surrounding seed oils centers on their fatty acid composition, particularly their omega-6 content. Omega-6 fatty acids are essential to human health, but critics argue that modern diets contain them in excess relative to omega-3s, potentially contributing to inflammatory pathways.

At the same time, seed oils are frequently grouped together with ultra-processed foods, creating the assumption that they are inherently damaged, unstable, or degraded during manufacturing. Blanket statements such as “seed oils are toxic” or “seed oils cause inflammation” circulate widely, despite a lack of consistent clinical evidence supporting these claims when oils are consumed within typical dietary patterns.

What is often missing from this discussion is how oils are refined, stored, protected, and used. These factors have a far greater impact on stability and quality than whether an oil comes from a seed.

Why Seed Oils Became Popular in Food Manufacturing

Seed oils did not become ubiquitous by accident—they solved real and persistent challenges in food production.

As packaged and shelf-stable foods expanded rapidly in the mid-20th century, manufacturers needed fats that were scalable, cost-effective, consistent, and reliable. Seed oils such as soybean, corn, sunflower, and canola met those needs. They were supported by established agricultural infrastructure, could be refined to neutral sensory profiles, and behaved predictably during processing.

Equally important, seed oils enabled longer shelf life. Compared to animal fats, which introduce variability in flavor, sourcing, and stability, refined seed oils offered cleaner taste, better oxidative control, and improved compatibility with antioxidants and modern packaging systems.

Their widespread adoption was driven by function, economics, and food safety—not ideology.

Oxidation: The Issue Consumers Are Actually Sensing

Oxidation is the chemical process by which fats degrade when exposed to oxygen, heat, or light. As oxidation progresses, oils develop off-flavors, unpleasant aromas, and reduced functional performance—what consumers recognize as rancidity.

This is where some concerns about seed oils intersect with reality, but are often oversimplified.

Oils higher in polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), including many traditional seed oils, are more chemically reactive than saturated or monounsaturated fats. That increased reactivity means they require more thoughtful handling, refinement, and protection to maintain stability over time.

However, oxidation is not unique to seed oils. Animal fats, butter, ghee, and olive oil can oxidize—and in some applications, they do so more quickly. Free fatty acid levels, exposure to light, oxygen permeability of packaging, and storage conditions all play a critical role in how fast rancidity develops.

In other words, oxidation is a chemistry issue, not a branding issue.

Why “Just Use Olive Oil or Tallow” Isn’t So Simple

As seed oils fall out of favor in consumer conversations, alternatives like olive oil, butter, ghee, and tallow are often positioned as universally better solutions. In commercial food systems, each comes with real limitations.

Animal fats introduce dietary, religious, allergen, and labeling constraints that many CPG brands cannot accommodate. They also vary widely in flavor, sourcing consistency, and oxidative stability depending on refinement and handling.

Olive oil, while widely perceived as a premium or “gold standard” fat, is expensive, supply-constrained, and often unsuitable for dry seasoning systems, encapsulated formats, or high-heat applications. It is also particularly sensitive to oxygen exposure, making it prone to flavor degradation and rancidity in many shelf-stable environments.

From a formulation standpoint, fat selection is about performance, shelf life, cost-in-use, and regulatory realities—not ideology.

Sunflower Oil: Still a Seed Oil—But Not All Seed Oils Are Equal

Yes, sunflower oil is a seed oil—but grouping all seed oils together ignores meaningful differences in fatty acid composition.

High-oleic sunflower oil, for example, contains significantly higher levels of monounsaturated fats and lower levels of PUFAs compared to traditional sunflower oil. This makes it far more oxidatively stable and better suited for applications where shelf life and flavor integrity matter.

This distinction highlights the real issue: the problem is not “seed oil” as a category—it is oxidation management.

How Oxidation Is Managed in Commercial Food Systems

In food manufacturing, oils are never used in isolation. Oxidation control is achieved through a layered approach that includes selecting oils with appropriate fatty acid profiles, refining and deodorization standards, antioxidant systems (natural or synthetic), encapsulation or carrier protection, oxygen-controlled packaging, and strict storage and distribution protocols.

When these elements work together, seed oils can perform reliably in shelf-stable products without contributing to off-notes or premature rancidity. Conversely, removing seed oils without addressing oxidation holistically can shorten shelf life—even when replacement fats are perceived as more “natural.”

What This Means for Shelf-Life Expectations

Rancidity is not caused by a single ingredient—it is caused by exposure, imbalance, and insufficient protection.

Any product containing fat requires realistic shelf-life expectations based on formulation design, packaging, and distribution conditions. Eliminating seed oils without addressing oxidation at a systems level often creates new quality issues rather than solving existing ones.

For brands, building consumer trust means educating rather than reacting.

Setting the Record Straight

The backlash against seed oils reflects a broader desire for transparency and understanding—and that is a positive shift. But reducing complex food chemistry to good-versus-bad ingredient lists oversimplifies reality and limits innovation.

The real conversation is not whether seed oils are “bad.” It is whether fats are selected intentionally, protected appropriately, and used responsibly within a formulation.

When oxidation is properly managed, shelf-stable foods can deliver safety, flavor, and performance—without sacrificing quality or consumer trust.

Let’s Talk About What Actually Works

If you’re navigating fat systems, shelf-life expectations, or reformulation pressure driven by seed oil concerns, the right solution isn’t a one-size-fits-all swap. It’s a formulation strategy that considers oxidation, stability, labeling, cost-in-use, and real-world distribution. At NuSpice, we work alongside product developers and brand teams to evaluate fat systems holistically—so performance, flavor, and shelf life stay intact while meeting today’s consumer expectations. If you’re questioning your current approach, we’re here to help you make informed, practical decisions.