Two weeks ago we introduced the first contender in our battle of the spices, the Szechuan Peppercorn. Read all about the berry with a zing here. Is it a match for the root with a rare bite in the snoot, Wasabi?

Wasabi is a plant from the Brassicaceae family. You might be familiar with some its family members, like mustard and horseradish. The traditional wasabi refers to a specific part of the plant, the rhizome (“rīˌzōm”) or root stem. Examples of rhizomes include ginger and turmeric.

Wasabi root is one of the rarest crops in the world and thus one of the most expensive. It is reported that as much as 99 percent of the wasabi sold in the United States is imitation wasabi. Experts estimate that 95 percent of the wasabi sold in Japan is imitation, as well.

There are several reasons why wasabi is so rare. The number one reason is that wasabi is incredibly difficult to grow. In its native Japan, it grows naturally in coastal mountains, in the bottom of dark forested canyons. Nestled in temperate rainforests, next to sandy river bottoms or directly in shallow creeks and rocky pools, wasabi thrives.

But it also needs continual running spring water. The correct pH balance in the soil, and year-round temperatures ranging from 46° to 68° Fahrenheit. All these conditions are exceedingly difficult to replicate naturally. Wasabi wilts in small amounts of sunshine or at high temperatures. It stops growing completely in cool fall weather. Any breakage of the brittle leaves by farmworkers or animals can slow its growth. Also, wild animals like deer will eat the wasabi leaves. Thus, the area needs to be fenced off to keep out the animals.

Cultivating Wasabi Root

Before you can even begin to think about growing this rare root, wasabi cultivation requires a special “washing” of the soil. The risk of disease rises when accumulated organic matter, such as dead insects and decayed leaves, stagnates the flow of the water. To prevent this, the surface soil is turned over and carefully washed with a sprayer.

Once the wasabi root is planted, you have another problem. Wasabi is unlike other crops that mature on a three-month cycle. Wasabi needs two to three years to fully grow. This takes up land and resources, and increases the chances where things can go wrong. A flood can wash out a whole wasabi crop plus, severely damage the farm itself.

Small Scale Farms

Another problem is farm size. Because spring water is essential for growing wasabi, wasabi farms are concentrated in mountainous areas. These farms are inevitably “small-scale farms” by Japanese standards. The Japanese Food, Agriculture, and Rural Areas Basic Act was enacted in 1999 and focuses on farms of ten acres or more. Under this act, wasabi farms across Japan are too small to receive subsidies. Even the largest of them, which owns wasabi fields in both Utogi and Yamanashi Prefecture, has a total acreage of no more than one and a half acres. Without the support from the Japanese government, many traditional wasabi farms have been abandoned. Some of this has been caused by a 50% decline in population in the mountainous area over the past years.

And if that is not enough, wasabi is not a very fertile plant. First, it produces very few seeds and not all the seeds are fertile. You can plant a lot of seeds and not get many to sprout. Since insects do not like the wasabi pungent flavor, farmers need to hand pollinate every plant.

On top of that, freshly grated wasabi loses its flavor within ten or so minutes.

So, with all these restrictions there are few wasabi roots to begin with which drives up the price. As much as $200 for a single root, making it quite expensive. There’s also not much in circulation to buy, even if you are willing to pay the high price tag.

And once you have the real thing, it is hard to use. The root itself only last one day at room temperature and only a month in the refrigerator. In the refrigerator, the wasabi must be stored in water and the water must be changed every day. On top of that, freshly grated wasabi loses its flavor within ten or so minutes. This means the chef must wait till the last minute to hand grate the wasabi for the meal. The price, storage conditions, prep time, and poor shelf life makes it unpopular in most busy restaurants.

Traditional Farming Areas

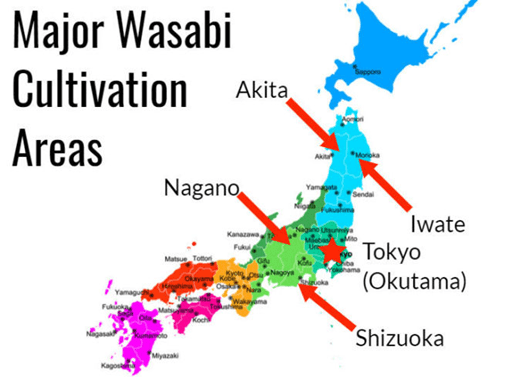

Given the rigid environmental requirements, wasabi is mainly grown commercially in certain rural mountainside regions. These regions include Japan’s Shizuoka prefecture, home to the Mt. Fuji, and in the Izu Peninsula. Wasabi is also commercially grown in the Nagano and Iwate prefectures.

There are several different styles of wasabi cultivation in Japan. Each is associated with differing qualities of wasabi rhizomes. It seems that each family farm has its own unique method past down for generations. Traditional methods typically rely on mineral-rich spring water instead of fertilizers and a lot of manual labor, making them environmentally friendly.

These mountainous fields are carefully designed with rocks and gravel. Therefore, replicating the plant’s natural waterfall-like habitat. It helps accommodate gentle flooding, and some have been in continuous production for hundreds of years. These farms produce larger high quality roots but in low volumes.

The modern methods grow the wasabi in irrigated fields along streams in large plantations. The roots are smaller, but these farms produce most of the wasabi crop.

Getting to the Root

The history of wasabi starts as far back as 16,000 years ago, during the Jōmon period in Japan. In this prehistoric era, which lasted from 14,000 BC to 400 BC, Japanese people largely lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, eating fish, seafood, deer, nuts, tubers, and amazingly, wasabi. Several archaeological excavations confirm that these ancient people were eating a wild, small-rooted, form of wasabi. As these hunter-gatherers grew into farmers, the practice of eating wild wasabi continued into the Heian period.

Archaeologists have also unearthed old signs from a 5th century academic garden. They documented wasabi as a medicinal plant since at least that era. The oldest Japanese herb encyclopedia, written in 918 AD, also mentions wasabi as medicinal. However, by the mid-Ashikaga period, which started in 1338 and lasted until 1573, the world of wasabi had changed. Now the wasabi plant was reserved for royalty and was served with raw fish.

How Wasabi Farming Spread

Tokugawa Ieyasu, a great shogun of the classical Edo period (between 1603 and 1867), was very fond of the herb. He fell in love with wasabi the moment he saw it, as the plant’s leaves bear striking resemblance to his family’s crest (the hollyhock). Because of this, the shogun encouraged the spread of wasabi in his domain, focusing on the mountain village of Utogi. The village survives to this day in modern-day Shizuoka prefecture and is still the center of wasabi farming in Japan. The actual field that the villagers used to first cultivate wasabi root was preserved and is still growing wasabi.

Historically much of Tokyo’s fresh wasabi is said to have been sourced from the mountainous region of Okutama, just outside the city limits. This area continues the tradition of wasabi farming to this day. Long ago, Okutama had several farms, many of which were said to have been made by people engaged primarily in forestry. In their spare time, they did the bulk of the backbreaking work of smashing boulders to build up terraces and irrigation ditches along mountain streams.

Though the individual farms were not particularly large, each with up to only around several hundred plants, in total they could produce a fair amount of crop. As years went by, many of the farmers gave up their trade or moved away as they aged. Thhe collapse of the forestry industry accelerated the exodus, while leftover Japanese cedars smother many of the old wasabi patches.

What Makes Wasabi So Spicy?

The best way to explain wasabi’s spice is to compare it to a more familiar source of heat: The chili pepper. A chili pepper gets its spiciness from a compound called capsaicin, which causes a reaction on our tongue (and by extension, our throat). The compound is named after the Capsicum plants, which evolved it as a defense mechanism to fight off fungi. Capsaicin is also very oily, which is why it lingers in our mouths no matter how hard we try to wash it out. You need another fat like a dairy product to remove it.

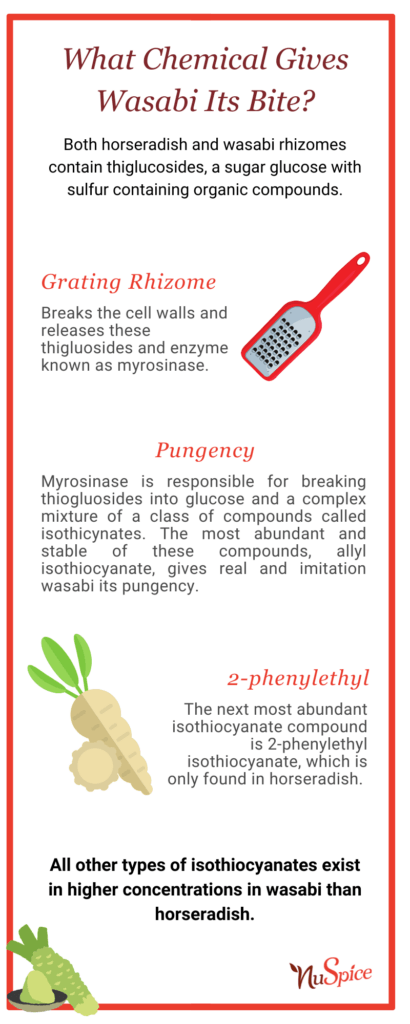

But wasabi root is different. Its spiciness comes and goes, and water quickly washes it away. Moreover, its heat doesn’t come from a defensive irritant. Instead, it comes from cellular enzymes mixing together. When wasabi’s cells are broken (like when a chef grates them) they start a chain reaction that results in a sulfuric, smelling salt sensation. his affects our mucus membranes causing our eyes to water and our nose to burn.

You also get this affect from horseradish and mustard seed, which are relatives to wasabi and have similar chemical reactions. That is why powdered horseradish and powdered mustard were chosen for imitation wasabi!

Medical Effects

Wasabi has been considered a medicinal herb for much of its history. In Japan, wasabi was first discovered and used for its medical features rather than for its taste.

One of the beneficial effects is that wasabi has proven to have antibacterial properties. A study from the journal Frontiers in Microbiology revealed that wasabi “has strong antibacterial property and has high potential to effectively control E. coli O157:H7 and S. aureus in foods.” Other studies have also suggested wasabi can soothe stomach ulcers. When administered to test subjects infected with the ulcer-causing bacteria H. pylori, it seems “wasabi leaves and AIT [allyl isothiocyanate] may provide a natural remedy for stomach lesions induced by H. pylori.”

Wasabi’s extracts also indicate it’s a strong anti-inflammatory agent. At least two studies have shown a clear effect on nerves (neuroinflammation) and white blood cells. In the past, consuming raw or uncooked food, such as “sashimi”, or thin-sliced raw fish or meat, could cause sickness and food poisoning.

Especially when sanitization and effective cures were a challenge a thousand years ago, and insects could easily spread dangerous bacteria. However, some Japanese discovered that they could avoid illness by eating raw food with wasabi.

The strong and spicy wasabi taste helped decrease the smell of raw fish and provided health benefits.

Also, when sushi was invented during the Edo period to help preserve fish, Japanese people used wasabi as a condiment to the dish. The strong and spicy wasabi taste helped decrease the smell of raw fish and provided health benefits. The practice became more common over time, and more people started implementing wasabi into their food. As it turns out, the very same enzyme that makes wasabi spicy, allyl isothiocyanate, helps combat food poisoning. Also, it produces several other health benefits.

Wasabi lives up to its status as a medicinal herb. It does way more than just clear your sinuses!

The Rise of Imitations

Because of the limiting growing conditions, wasabi farms stayed small well into the 20th century. As sushi restaurants began to spread around the world, the farmers simply couldn’t keep up with global demand. Inevitably, this led to the rise of cheap wasabi imitations.

As a result, today when you order wasabi with your sushi outside of Japan, expect to be served imitation wasabi. Imitation wasabi is horseradish with green coloring added, which is much cheaper to produce than real wasabi. Even in Japan, most consumers get cheap processed wasabi, which is made of imported wasabi-style horseradish. This type of wasabi-style horseradish comes in the form of a paste or powder, instead of the fresh wasabi root their ancient ancestors enjoyed.

If you are wondering how to tell the difference between real and fake wasabi, firstly check the texture of the wasabi paste. When the wasabi is thick and pasty, that is a sign that it is fake wasabi from horseradish (pureed to give a completely smooth texture). If the consistency is gritty from being freshly grated, then the more likely it is to be true wasabi from a wasabi plant root. Wasabi paste contains very little low-grade wasabi and has had artificial color added to it, giving it a brighter green appearance.

Also, real wasabi is always served fresh because it loses its flavor and punch quickly once grated. For example, at a high-end sushi restaurant, the chefs will wait till the last moment to carefully grate the exact amount of wasabi to complement the sushi. Wasabi at all-you-can-eat buffet bars that are left out in a bowl will never be real.

Lastly is the price tag. If you can afford it, it’s not real wasabi.

Awaken the Senses

The Ig Nobel Prizes are awarded annually for achievements that make people laugh, and then think – and the wasabi fire alarm, which was awarded the 2011 prize in chemistry, is a great example.

The Ig Nobel Chemistry Prize 2011: Makoto Imai, Naoki Urushihata, Hideki Tanemura, Yukinobu Tajima, Hideaki Goto, Koichiro Mizoguchi and Junichi Murakami of Japan, for determining the ideal density of airborne wasabi (pungent horseradish) to awaken sleeping people in case of a fire or other emergency, and for applying this knowledge to invent the wasabi alarm.

One thing that is active when we are asleep is our sense of irritation or pain in response to certain chemicals that are neither smell nor taste. The researchers found that breathing in air tainted with artificial wasabi essence (a chemical called allyl isothiocyanate) rapidly woke sleepers and brought people to alertness at least as fast as a siren.

The key was to use enough chemical to wake up the sleeper but not too much to incapacitate them so they could get out of the building.

This system also has potential to be used in very noisy environments and where crowds might ignore other alarms, such as in nightclubs. It consists of a standard smoke detector wired up to an automatic spray containing a can of the wasabi essence but could be expanded with more detectors and sprays to cover a wider area.

Final Note

Lastly powdered, imitation wasabi still makes up most of the market. But that could be changing. In recent years, several American and Canadian farms have begun producing fresh wasabi for the west. But for now, the output is low as wasabi continues to be a most difficult crop to harvest.

How do you think wasabi compares to Szechuan peppercorn? Let us know your thoughts on social media!